The mark left on the New World, or Turtle Island, by Hernan Cortez, left Ponce de Leon in the dust. Born a lesser noble with dim prospects, he headed to Hispaniola and then Cuba as a young man. Bogarting and elbowing his way upward, he received what was called an encomienda, a designated area of land with the command of all to non-Christian labor upon it. This was typical of all the nobility and many of the military who had migrated, and they put it to use to make their fortunes. Cortez used his allotment to work himself into a position to make a military invasion of what was the Aztec empire against the orders of Cuba's governor.

We all know the next part fairly well. Cortez impressed the first two native peoples with his horses and guns and thought they might use Cortez against the local rivals. So Cortez defeated one group after another, until he had gathered a considerable force, fought his way into Tenochtitlan, got Montezuma to agree to meet him, then put the Aztec ruler under house arrest. Cortez proceeded to take over the region and killed Montezuma along with his two chief underlings. This made Cortez head honcho, more or less, of what he called 'New Spain' with many subordinate states. But the Spanish king made Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar the governor of New Spain, with Cortez in a secondary position.

No matter. Cortez maneuvered his way back to the top. But what is interesting to us is how did, apart from looting Aztec royalty, Cortez and others like him make their money? The answer is silver, much more so than gold. Central Mexico had lots of it in the hills, in ore seams that reached the surface. Unlike gold, silver ore had to be treated and processed several times to leach out the silver. Moreover, the seams went downwards, requiring long shafts up to 600 feet.

This required a lot of labor. All was done by hand tools, wooden ladders, ropes, and headbands. It required a class of miners, made up of drafted Indians, enslaved Africans, and when they weren't enough of these, more Indians were recruited paid a wage. Cortez himself owned dozens of mines and hundreds more by other Spaniard settler-colonizers. Up to 5000 miners were forming the mixed slave and wage proletariat of New Spain. And as workers often do, they waged battles and strikes to improve their conditions. Sometimes they were killed and replaced. But since the work required some skill, sometimes they won a few actions. If you want to write our labor history, this is one good starting point.

The key point is there was constant pressure to find more slaves. This was made difficult because the successor to King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella, the young King Charles II, and Marianna, his regent mother, were trying to outlaw slavery in the Caribbean and New Spain, to make new 'Catholic vassals' of the peoples. Only about 10% were actually freed. But excuses had to be concocted to enslave new peoples.

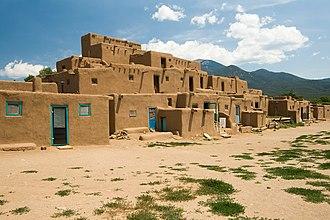

So next we find one Juan de Oñate y Salazar, a young conquistador of the late 1500s who married Cortez's granddaughter. He gathered up a small army and headed northward, to subdue a new area, the 'New Kingdom of León y Castilla,' later known as New Mexico in what is now the United States. In 1598, he crossed the Rio Grande and pressed on until he ran into a relatively large collection of Pueblos, the adobe city of the Acoma peoples. Oñate raids them for food and tries to capture slaves but meets resistance. It turned into a full-scale war, and the Acoma, only 500 left, surrendered. To punish any who won't be enslaved and work, he gathers dozens of young men and chops off one foot (some reports say he chopped off their toes).

Oñate took his troops far beyond Santa Fe, exploring and capturing native peoples into what is now Oklahoma and Texas. Eventually, news of his cruelties caught up with him, and in 1608, he went back to Mexico. But he's still remembered. When Hispanic New Mexicans recently tried to commemorate him with a statue, indigenous New Mexicans wanted it removed. Someone cut off one foot of the statue's horse where he was seated. Some memories stick around.

Some 80 years later, the Pueblo people's organized a general uprising and drove the Spaniards out for 12 years. Its leader was named Po'pay, and the revolt is often named after him. Today's New Mexicans have a statue of him in the U.S. Congress. More to come.

No comments:

Post a Comment