The southern Lenni Lenape lived in the watershed of the large river flowing into a major bay, both now called the Delaware. Several other rivers, now called the Schuylkill and the Lehigh, were tributaries flowing into the Delaware river not far from the Bay. 'Lenni Lenape,' in their own language, had a double meaning, both 'common people' and 'original people.' It made sense since study has shown they had been there for a very long time, perhaps migrating there some 10,000 years ago, until they reached the end of the land and the Atlantic seacoast.

Wednesday, October 27, 2021

NEW NARRATIVE #12: The Lenape, William Penn and 'Culture Clashes'

The southern Lenni Lenape lived in the watershed of the large river flowing into a major bay, both now called the Delaware. Several other rivers, now called the Schuylkill and the Lehigh, were tributaries flowing into the Delaware river not far from the Bay. 'Lenni Lenape,' in their own language, had a double meaning, both 'common people' and 'original people.' It made sense since study has shown they had been there for a very long time, perhaps migrating there some 10,000 years ago, until they reached the end of the land and the Atlantic seacoast.

Posted by

Carl Davidson

at

6:11 AM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Friday, October 22, 2021

New Narrative #11: The Lenape, New Sweden, and a Socialist Experiment

The area, which we now call Delaware Bay, after Baron Del A Warr, aka Thomas West, a great-grandson of Mary Boleyn, sister to Ann, the consort of Henry VIII. West was assigned a number of posts in Turtle Island but didn't fare well in any of them. Sickness got the better of him, and he returned to England, not leaving behind much more than his royal name.

The English were far from the first visitors to the Lenape. In 1521, Francisco Gordillo and a slave trader Captain Pedro de Quejo (de Quexo), representing Holy Roman Emperor Charles the Fifth (King of Spain and Austria), toured the area but left little than a new name, 'St. Christopher's Bay.' They were followed by a Dutch explorer, Cornelius Jacobsen May, who left his name on Cape May, the seaward edge of the bay. He actually managed some trade with the Lenape there but moved north to New Amsterdam and the Hudson River.

Next, it's Sweden's turn. The Kingdom of Sweden, recently expanded after success in a few European wars, decided to try its hand in taking a piece of the New World. Two ships, Kalmar Nyckel and Fogel Grip, set sail and landed in 1638 in Delaware Bay. They set up Fort Christiana, named for their Queen, near to what is now Wilmington, DE. They unloaded both Swedish and Finnish families in the area, and also further up the Jersey side to the river, staking out Fort Elfsborg.

Despite the forts, the settlers in New Sweden were far from militarized. In a way, it worked to their advantage. They were compelled simply to trade with the Lenape, and come to agreements about land use amicably. The Finns built their homes as log cabins, much as they had back in Finland, and it is sometimes claimed they were responsible for 'inventing' them for the New World. Perhaps a good many settlers copied them, but the Cherokee and other native peoples had log cabins far from New Sweden.

In any case, New Sweden was thriving and growing. But from the beginning, the Dutch were annoyed by the Swedish colony on land they assumed belonged to them. In 1655 Peter Stuyvesant sent several ships with militia to take them over. Given the settler's weakness and lack of powder, the skirmishing ended quickly, and New Sweden was absorbed into New Netherlands. On the ground, though, it meant little, as Swedes and Finns continued to arrive and settle all around the eastern edge of the bay and up the Delaware River. But Sweden decided to let it go, as not worth another war.

Our story wouldn't be complete, however, without a mention of Pieter Cornelisz Plockhoy, a Dutchman, some claim as 'the father of modern socialism.' Plockhoy had devised a plan for a cooperative settlement near Ft Christiana, where worker-members would divide their labor according to their skills, run the project themselves, establish a six-hour day, and equally divide the profits each year. It was set up at Hoorn Kill on the Delaware River, near Swannendaal (New Castle). It reportedly did rather well until 1664, when the English took over New Netherland, including the former New Sweden, changed the name to New York and New Jersey, plundered and looted the coop settlement, and sent Plockhoy off live with Quakers, in what is now Philadelphia. More to come.

Posted by

Carl Davidson

at

3:19 PM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Tuesday, October 19, 2021

NEW NARRATIVE #10 The Mohicans, Henry Hudson, and New Netherlands

Posted by

Carl Davidson

at

5:55 AM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Saturday, October 16, 2021

NEW NARRATIVE #9: Squanto, the Plymouth Colony and King Phillips War

Posted by

Carl Davidson

at

3:51 PM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

NEW NARRATIVE #8: Powhattan, Jamestown and Tobacco

Posted by

Carl Davidson

at

3:45 PM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

NEW NARRATIVE #7: New Albion, Roanoke and the Queen's Pirates

Posted by

Carl Davidson

at

3:28 PM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

NEW NARRATIVE #6: New France and the Fur Trade

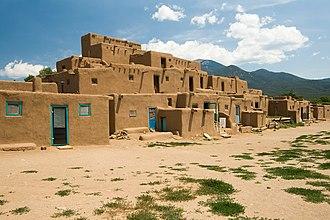

It's time to turn to other European powers, starting with France. We've established St Augustine, Florida, and Santa Fe, New Mexico as the first permanent European settlements in what is now the USAmerican part of 'Turtle Island' or North America.

Posted by

Carl Davidson

at

3:21 PM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

NEW NARRATIVE #5: Cortez, Mexico and the Enslaved Proletariat Mining Silver

Posted by

Carl Davidson

at

3:18 PM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

NEW NARRATIVE #4: Enslaved Tainos Miners and Ponce De Leon's Florida Raids

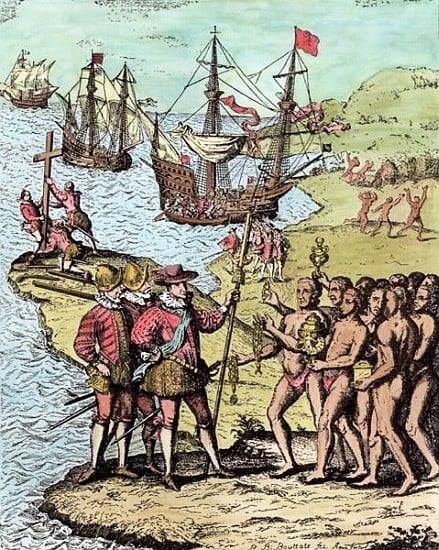

Columbus and a cohort of enslavers and settler-colonialists didn't come to the Caribbean for sightseeing. They wanted wealth, and lots of it, for themselves and the Spanish Court. Without much immediate gold or spices to be taken, Columbus enslaved and sent back people. First, he sends a few dozens, then a batch of 400 or so, in horrific conditions on board the ships. While the Court at first accepted them as curiosities, Queen Isabella didn't like dealing in slaves herself, so she turned them out to be sold in the local markets.

Posted by

Carl Davidson

at

3:16 PM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

New Narrative #3: The Basques Fish for Cod, Columbus Arrives in Indies

Posted by

Carl Davidson

at

3:13 PM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

NEW NARRATIVE #2: The Pope and the 'Law of Discovery'

Posted by

Carl Davidson

at

3:09 PM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

A NEW NARRATIVE #1: The Civilizations of 'Turtle Island'

Posted by

Carl Davidson

at

3:05 PM

0

comments

![]()

![]()